| ||

| HMS Euryalus |

Monday, October 21st 1805

A.M. - At 12.30, set foresail. At 4, out one reef of the topsails.

Light breezes and hazy. At daylight, the body of the enemy's fleet ESE

5 or 6 miles. English fleet WSW. At 8, observed the British

fleet forming their lines, the headmost ships from the enemy's centre 8 or 9

miles. The enemy's force consisting of thirty-three sail of the line,

five frigates and two brigs. Light winds and hazy with a great swell

from the westward. English fleet all sail set. Standing towards

the enemy, then on the starboard tack. At 8.5, answered Lord Nelson's

signal for the captain, who went immediately on board the Victory.

Took our station on the Victory's larboard quarter and repeated the

Admiral's signals. At 10, observed the enemy wearing and coming to the

wind on the larboard tack. At 11.40, repeated Lord Nelson's telegraph

message: 'I intend to push or go through the end of the enemy's line to

prevent them from getting into Cadiz.' Saw the land bearing E by N, 5

or 6 leagues. At 11.56, repeated Lord Nelson's telegraph message:

'England expects that every man will do his duty.' At

noon, light winds and a great swell from the westward. Observed the

Royal Sovereign, Admiral Collingwood, leading the lee line, bearing down on

the enemy's rear line, being then nearly within gunshot of them. Lord

Nelson, leading the weather line, bore down on the enemy's centre.

Captain Blackwood returned from the Victory. Cape Trafalgar SE by E,

about 5 leagues.  |

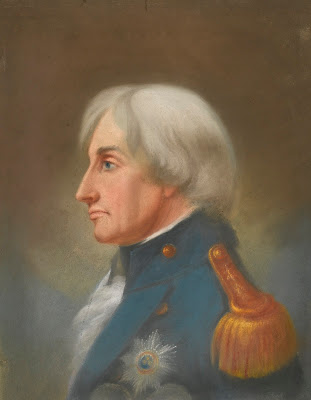

| The page of the log upon which Nelson's most famous signal was recorded. With thanks to The Lloyd's Collection. Please do not reuse this image without contacting me first. |

P.M. - Light winds and hazy. British fleet bearing down in two lines on the enemy's, which was forming in one line from NNE to SSE, their strongest force from the van to the centre. At 12.15, the British fleet bearing down on the enemy, Vice-Admiral Lord Viscount Nelson leading the weather line in the Victory, and Vice-Admiral Collingwood the lee line. At 12.15, the enemy opened a heavy fire upon the Royal Sovereign. At 12.16, the English Admirals hoisted their respective flags and the fleet, the British fleet, the British ensign (white). At 12.17, Admiral Collingwood returned the enemy's fire in a brave and steady manner. At 12.20, we repeated Lord Nelson's signal for the British fleet to engage close, which was answered by the whole fleet. At 12.21, the van and centre of the enemy's line opened a heavy fire upon the Victory and the ships she was leading into action. At 12.22, Admiral Collingwood and the headmost ships of his line broke through the rear of the enemy's, where the action commenced in a most severe and determined manner. At 12.23, Lord Nelson returned the enemy's fire in the centre and van in a determined, cool and steady manner. At 12.24, Lord Nelson and the headmost of the line he led into action, broke into the van and centre of the enemy's line and commenced the action in that quarter in a steady and gallant manner. Observed the Africa coming into the line, she being to leeward, with all sails set on the starboard tack (free). We kept Lord Nelson's signal flying at the main royal mast head, for the British fleet to engage close. At 12.26, observed one of the French ships totally dismasted about the centre of the line, by some of the ships of our lee line, and another of them with her fore yard and mizen topmast shot away. At 1.15, observed the Tonnant's fore top-mast shot away. At 1.32, her main yard shot away. The centre and rear of the enemy's line hard pressed in action. At 2, the Africa engaged very close a French 2-decked ship, and in about 5 minutes' time, shot away her main and mizen masts. At 2.10, observed the Mars hard pressed in action. The remainder of the British fleet, which were come into action, kept up a well-directed fire on the enemy. At 2.15, the Neptune, supported by the Colossus, opened a heavy fire upon the Santisima Trinidad and 2 other of the enemy's line which were next her. At 2.20, The Trinidad's main and mizen masts were shot away. At 2.30, the Africa shot away the fore mast of the 2-decked ship she was engaged with, and left her a complete wreck. She then bore up under the Trinidad's stern and raked her fore and aft. Colossus and Neptune still engaged with her and the other two ships, which appeared by their colours to be French. At 2.34, the Trinidad's fore mast shot away, and at 2.26 one of the French ships' main and mizen masts. Observed 9 of the enemy's van wear and stand down towards the centre. Observed the Royal Sovereign with her main and mizen masts gone. At 2.36, answered Lord Nelson's signal to pass within hail, made all possible sail and made the signal to the Sirius, Phoebe and Naiad to take ships in tow which were disabled ENE, which she answered. Sounded in 50 fathoms. At 2.40, observed a French 2-decked ship on fire and dismasted in the SSE quarter. Passed the Spartiate and another 2-deck ship standing towards the enemy's van and opened a heavy fire, when the action in that quarter commenced very severe. At 2.50, passed by the Mars, who hailed us to take them in tow. Captain Blackwood answered that he would do it with pleasure, but that he was going to take the second in command, the Royal Sovereign. The officer that hailed us from the Mars, said that Captain Duff was no more. At 3, came alongside the Royal Sovereign and took her in tow. Captain Blackwood was hailed by Admiral Collingwood and ordered to go on board the Santa Ana, Spanish 3-deck ship, and bring him the Admiral, which Captain Blackwood obeyed. At 3.30, the enemy's van approached as far as the centre and opened a heavy fire on the Victory, Neptune, Spartiate, Colossus, Mars, Africa, Agamemnon and Royal Sovereign, which we had in tow, and was most nobly returned. We had several of our main and topmast rigging cut away, and backstays by the enemy's shot, and there being no time to haul down the studdingsails, as the enemy's van ships hauled up for us, we cut them away and let them go overboard, at which time one of the enemy's nearest ships to us was totally dismasted. At 4, light variable winds; not possible to manage the Royal Sovereign, so as to bring her broadside to bear upon the enemy's ships. At 4.10, we had the stream cable, by which the Royal Sovereign was towed, shot away and a cutter from the quarter. Wore ship, and stood for the Victory. Observed the Phoebe and Sirius and Naiad coming into the centre and taking some of the disabled ships in tow. At this time the firing ceased a little. At 4.20, observed a Spanish two-deck ship dismasted and struck to one of our ships. Observed several of the enemy's ships still hard engaged. At 5, _ of the enemy's van and _ of their rear bore up and made all sail to the northward; were closely followed by the English, which opened a heavy fire upon them and dismasted a French two-deck ship and a Spanish two-deck ship. At 5.20, the Achille, French two-deck ship, which was on fire, blew up with a great explosion. At 5.25, made sail for the Royal Sovereign. Observed the Victory's mizen mast go overboard, about which time the firing ceased, leaving the English fleet conquerors, with _ sail of the enemy's ships in our possession and one blown up, _ of which were first rates, and all dismasted. At 5.55, Admiral Collingwood came on board and hoisted his flag (blue at the fore). At 6.15, sent a spare shroud hawser on board the Royal Sovereign and took her in tow, and at the same time sent all our boats with orders from Admiral Collingwood to all the English ships we could discover near us that they were to take the captured ships in tow and follow the Admiral. At the time saw Cape Trafalgar bearing SE by E about 8 miles. Sent a boat on board the Spanish three-deck ship which had struck, one main topgallant sail, standing jib and main topgallant stay-sail. At 7.36, took aback, and the Royal Sovereign fell on board of our starboard beam, and there being a great swell she damaged the main channels, took away the lanyards of the main and mizen rigging, jolly-boat from the quarter and davits, the most of the quarter-deck and waist hammock cloths, boards, railing, with a number of hammocks and bedding; took away the main and mizen topgallant masts, lost the royals and yards. Tore the fore and main sails very much, and took away a great part of the running rigging. At 7.40 got her clear, made sail on the starboard tack with a light wind from the WSW, and a great swell. Employed repairing the damages sustained by the Sovereign falling on board of us. At 9, sounded in 23 fathoms. Made the signal with a gun, prepare to anchor. Fleet and prizes in company. Light airs and a great swell from the westward. At 9.15, sounded in 15 fathoms. At 9.2, in 14 fathoms. At 9.35, the water deepened. At 11, sounded in 36 fathoms. At 11.20, the water shoaled to 26 fathoms. At 12, in 22 fathoms.